I've posted a couple of past columns concluding that humans,

ultimately, are not as rational as we like to think ourselves to be. What we are, I believe, is pattern seekers,

and that's the basis of intuition. You

suddenly realize that one thing is like another--like Newton's realization that

the falling apple and the earth's moon were bound by the same force, or Philo

Farnsworth's inspiration for television from watching a till in the soil. It's a sudden insight, an epiphany. And fundamentally, it's irrational.

But that brings me to another kind of

irrationality: irrational numbers. Belatedly, I learned that March 14 is known as

π day. π, the lower case Greek letter pi, is equal to 3.14159265359…, and

March 14 or 3/14 which is an estimate of π to two decimal places has been

designated Pi Day.

π is an irrational number. It just goes on without repeating for ever

and ever.

There are lots of irrational numbers. As a matter of fact there is a famous,

elegant proof by mathematician Georg Cantor showing that the set of irrational

numbers is larger than the set of rational numbers. That's a lot of irrational

numbers considering there are an infinite number of rational numbers. Cantor showed there are different sizes of infinity.

But that's another Mindfingers post.

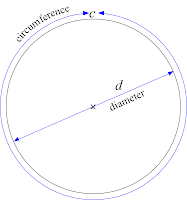

π is perhaps the most famous example of an

irrational number, and almost certainly the first one practically used. π is simply the number of times a diameter

goes into the circumference of a circle.

That is, if you took the diameter, D, in the circle below and wrapped it

around the Circumference, C, it would go just over three times—π times to be

exact.

Circles, of course, are

important, now as in antiquity. The moon

is a circle. The wheel is a circle. π was the magic number that would turn

straight lines into circles. It was

known back as far as the Babylonians and Ancient Egyptians.

Despite the fact that π has been proved to

be an irrational number, this hasn’t stopped people from trying to patterns

within it. It has been expanded to around ten trillion decimal places, last I

checked. People are forever counting how

many 5's there are, or where certain combinations of numbers appear. There are oodles of “sacred geometry” websites professing spiritual revelation out of the understanding of π and

other important irrational numbers.

Of

course, since π just keeps going, it does have the exact phone numbers,

consecutively and in alphabetical order, of everyone who has read this post.

But in fact, π is not without pattern. If it's

written in its decimal format, it looks that way, but there are other ways to write

numbers. As an infinite series for

example:

Looking at that, π appears quite elegant

actually. It's an accurate

representation of π, but it's not very efficient. To get π to 10 measly decimal places, you'd

have to expand that series to 5 billion terms.

There are other infinite series that converge on π much more quickly, but they

lack elegance of the above. This one converges

very quickly, but isn't quite as nice to look at:

|

| Messy. Looks impressive though, right? And it's hypogeometric. That sounds important! |

The above mess was the work of Srinivasa

Ramanujan, a self-schooled brilliant mathematician from one of the poorest parts

of India in the late-19th / early-20th century who, with

practically no formal training in mathematics, wrote to Cambridge professor of

mathematics G.H. Hardy about his work on infinite series and continued

fractions. Hardy, after reading the unsolicited work Ramanujan, was completely

out of his depth. He famously said that

the theorems in Ramanujan's treatise "must be true, because, if they were

not true, no one would have the imagination to invent them." Ramanujan went on to a storied tenure at Cambridge University and made phenomenal

contributions to mathematics. He died at

32, probably in no small part due to chronic malnutrition and disease as a

youngster.

pic of Ramanaujan.

|

| Srinivasa Ramanujan: "An equation for me has no meaning, unless it represents a thought of God." |

Another way of articulate a number is

through continuing fractions, where π can be represented as:

These numbers, like humans, may be

irrational, but they certainly aren't unintuitive. They have patterns that can't be seen in a

simple decimal expansion. The patterns

can only be seen when you include infinity--such as infinite series or

continued fractions. Rather pretty

patterns, and restoring my faith in the underlying elegance of the

universe.

Without getting too geeky (I know, I

know--too late), one of the most beautiful equations in mathematics is known as

Euler's Identity. I've even seen a tattoo of it.

Here, e

is the natural exponent. If you've ever

done much work on growth of bacteria, half-life of radiation, or compound

interest, you may have come across it.

It's the "base unit" if you will, of exponential growth or

decay. And, like π, it's

irrational. 2.718281828...

The term i is the square root of -1. But, of course, negative numbers can't have

square roots which is why i stands

for "imaginary number."

So you take one irrational number, e, take it to the power of another

irrational number, π, times the imaginary square root of negative one, subtract

1 (known as "the multiplicative identity" in mathematics) and you get

0 (known as "the additive identity" in mathematics). It ties together a number of disparate

mathematical terms and concepts in an equation of breathtaking eloquence and

simplicity.

Let's close off with a little brain

teaser. What's the solution to the

infinite series below. Answer next time.